|

National parks in central Africa have closed to protect vulnerable gorilla, chimpanzee, and bonobo populations from COVID-19. Because great apes are closely related to humans and have been both the source and the recipient of human viruses previously, national parks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda are closing for the time being to protect their endangered primate populations, which are a significant source of tourism revenue. Uganda is considering doing the same. (South Africa has also closed its national parks as part of its country-wide lockdown.) news.mongabay.com/2020/03/national-parks-in-africa-shutter-over-covid-19-threat-to-great-apes/

0 Comments

This map from a major health care provider shows the availability of intensive care unit (ICU) beds in the United States, by county. The counties in orange have no ICU beds. The counties in gray have no hospitals (!). The counties that fall into these categories are disproportionately rural and older. The article also addresses the huge variability in the number of ICU beds per resident in those counties that do have some ICU capacity (shown in blue) and has a searchable data table that allows users to compare ICU beds, population, and population age 60+ by county. khn.org/news/as-coronavirus-spreads-widely-millions-of-older-americans-live-in-counties-with-no-icu-beds/

I normally never do reruns, but I just used this article with my "From the Headlines" class and thought it was worth re-posting now. When I ran it in May 2017, the issue in the news was the new ebola vaccine. Today, it is worth reconsidering in the context of COVID-19: sooner or later, there will be a vaccine and, initially at least, that vaccine will be in short supply. In an epidemic, when there's not enough vaccine to go around, who gets the vaccine? Are some people more important than others on utilitarian grounds? Or because they're young? Or vulnerable? Or good? Or should access to vaccines, like other scarce resources, be determined by power or money or connections? This article, by an Australian philosopher who specializes in ethics and public health, teases apart some of these issues: "How Do We Choose Who Gets the Flu Vaccine in a Pandemic: Paramedics, Prisoners or the Public?" https://theconversation.com/how-do-we-choose-who-gets-the-flu-vaccine-in-a-pandemic-paramedics-prisoners-or-the-public-74164

According to UNESCO, an estimated 1.4 billion students are not currently in school because of coronavirus containment measures. This is roughly half the world's student population. This map shows where school closures are in force: www.statista.com/chart/21225/countries-with-country-wide-or-localized-school-closures

How can poetry be used to channel student reactions to current events? The Pulitzer Center is sponsoring a contest inviting K-12 students, from the U.S. and around the world, to read news stories on the Pulitzer site and choose one to respond to with an original poem. Entries are due by May 15. pulitzercenter.org/builder/lesson/fighting-words-poetry-response-current-events-contest-and-workshop-24262

A health-care company marketing "smart thermometers" can predict disease outbreaks weeks ahead of time by aggregating and mapping the data. After all, people start taking their temperatures before they ever show up sick in their doctors' offices. At present Kinsa Health is showing a high level of anomalous fever readings in Florida, suggesting a surge of flu-like illnesses may be imminent. healthweather.us/

In the category of unintended coronavirus consequences, public health data suggest that by dramatically reducing air pollution, COVID-19 may have, thus far at least, saved more lives than it has taken. According to this article from ScienceAlert, "[T]he number of deaths and the loss in life expectancy from air pollution rival the effect of tobacco smoking and are much higher than other causes of death." Stanford environmental economist Marshall Burke recently estimated that two months of reduced air pollution in China "has probably saved the lives of 4,000 children under 5 and 73,000 adults over 70 in China. That's significantly more than the current global death toll from the virus itself." This should spark serious conversation about pollution reduction efforts going forward. www.sciencealert.com/here-s-what-covid-19-is-doing-to-our-pollution-levels

This article explains current research to understand Thwaites, the world's "riskiest" and "most important" glacier, according to some scientists. "A complex interplay of topography, climatic change and ocean currents have coalesced to make the western regions of Antarctica (where Thwaites is situated) particularly vulnerable. Topography is critical when it comes to the reasons why Thwaites is acutely exposed. Antarctica is often split into East and West – not simply to make the vast continent easier to represent but because there are fundamental differences between the regions. ‘East Antarctica is principally a large continent with mountain ranges and thick ice, but west Antarctica is more like an archipelago of islands – predominantly below sea level and vulnerable to change,’ explains [Andy] Smith [a senior glaciologist at the British Antarctic Survey]. The increased presence of warmer water, carried towards the southern polar regions by ocean conveyors, is exacerbating issues. Usually, the continental shelf keeps the warm water in the deep ocean surrounding the continent. In recent decades, however, more warm water has got over the continental shelf and flowed down towards the ice. If the warm water thins the ice, it also opens up a larger gap underneath the sheet, exposing more of the underlying ice and potentially precipitating an accelerated rate of retreat. Thwaites is of particular interest not only due to its scale and the underlying topography but also due to what it is supporting. ‘Thwaites has access to a massive inland reservoir of ice and so changes to Thwaites could affect the whole ice sheet,’ says Smith. ‘Other glaciers are still important, but they don’t have the same potential to have such a significant impact on sea level rise.’ Ice draining from Thwaites accounts for approximately four per cent of global sea-level rise and the collapse of the glacier could potentially cause global sea levels to rise by up to 80cm." geographical.co.uk/nature/polar/item/3606-investigating-thwaites-the-riskiest-glacier-on-earth

These maps from a recent New York Times article look at "upmarket bubbles" (locations that are five miles or less from a Whole Foods, Lululemon, Apple store, or Urban Outfitters) vs. "down-home zones" (locations that are at least five miles from an upmarket bubble and within 10 miles of a Bass Pro Shop, Hobby Lobby, Cracker Barrel, or Tractor Supply). In 2016, 34% of American voters lived in an upmarket bubble and 50% lived in a down-home zone. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/02/27/upshot/democrats-may-need-to-break-out-of-the-whole-foods-bubble.html

Is it better to know? Or to want to know? Both knowing and wanting to know is ideal, but, according to this philosophy lecturer, in confronting the unknown, the intellectual traits associated with wanting to know may serve one better than possessing an answer will.

"Imagine the following. You are living a life with enough money and health and time so as to allow an hour or two of careless relaxation, sitting on the sofa at the end of the day in front of a large television, half-heartedly watching a documentary about solar energy with a glass of wine and scrolling through your phone. You happen to hear a fact about climate change, something to do with recent emission figures. Now, on that same night, a friend who is struggling to meet her financial commitments has just arrived at her second job and misses out on the documentary (and the relaxation). Later in the week, when the two of you meet for a drink and your friend is ignorant of recent emission figures, what kind of intellectual or moral superiority is really justified on your part? This example is designed to show that knowledge of the truth might very well have nothing to do with our own efforts or character. Many are born into severe poverty with a slim chance at a good education, and others grow up in religious or social communities that prohibit certain lines of enquiry. Others still face restrictions because of language, transport, money, sickness, technology, bad luck and so on. The truth, for various reasons, is much harder to access at these times. At the opposite end of the scale, some are effectively handed the truth about some matter as if it were a mint on their pillow, pleasantly materialising and not a big deal. Pride in this mere knowledge of the truth ignores the way in which some people come to possess it without any care or effort, and the way that others strive relentlessly against the odds for it and still miss out. ... "A good attitude towards knowledge shines through various character traits that put us in a healthy relationship with it. Philosophers call these traits epistemic virtues. ... Consider traits such as intellectual humility (a willingness to be wrong), intellectual courage (to pursue truths that make us uncomfortable), open-mindedness (to contemplate all sides of the argument, limiting preconceptions), and curiosity (to be continually seeking). You can see that the person ready to correct herself, courageous in her pursuit of the truth, open-minded in her deliberation, and driven by a deep curiosity has a better relationship to truth even where she occasionally fails to obtain it than does the indifferent person who is occasionally handed the truth on a silver platter. ... The consistent posture of seeking the truth gives us the best shot at seeing clearly, and that is what we should praise and value." https://aeon.co/ideas/would-you-rather-have-a-fish-or-know-how-to-fish This geo-graphic compares the ratio of beds in hospital critical care units to population across a sampling of countries. (It is interesting to note that in some cases, the data is eight or more years old, suggesting actual capacity may not be precisely known.) https://www.statista.com/chart/21105/number-of-critical-care-beds-per-100000-inhabitants/

The National Geographic Society just canceled this year's state and national geography bees for the first time in the bee's 32-year-history 😕. If you want to get a head start on learning about geography for next year, check out some of these free apps: Geo Bee Now for Android and iOS, Geography Quiz (by Peaksel) for Android and iOS, and the Ultimate Geography Quiz for Android.

The maps in this article tell the story of COVID-19. The interactive map at the end of the article, based on data collected by Johns Hopkins, is the best I have found for those interested in more-or-less real-time information. storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/4fdc0d03d3a34aa485de1fb0d2650ee0

What happens after the next two weeks? Or month? Or three months? This article by an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins considers the future of COVID-19.

"So the virus will traverse the world, probably infecting between 40 and 70 percent of the global population during its first wave. This might occur over a painful six to 12 months, or it might be spread over a more manageable several years. Either way, once the first wave is done, the virus is probably here to stay. ... We don’t know if infection with the novel coronavirus confers long-lasting immunity. If it does, then something similar will happen: Eventually, almost all adults will be immune, and new infections will be concentrated among children. Since the virus causes severe disease almost exclusively in older adults, this shift to a childhood infection would nearly, but not completely, eliminate hospitalizations and deaths from the virus. But none of the coronaviruses currently common in human populations confer lifelong immunity, and there is a very good chance that SARS-CoV-2 [aka, COVID-19] won’t, either. Still, subsequent infections with the virus will almost certainly be less severe than the first, as individuals accumulate partial immunity. This is similar to the incomplete protection you get when the flu vaccine is an imperfect match for circulating strains; you can still be infected, but the resulting illness is far less harsh. ... A buildup of population immunity will also moderate the yearly impact of the novel coronavirus in less obvious ways. Epidemics are like fires: When fuel is plentiful, they rage uncontrollably, and when it is scarce, they smolder slowly. Epidemiologists call this intensity the “force of infection,” and the fuel that drives it is the population’s susceptibility to the pathogen. As repeated waves of the epidemic reduce susceptibility (whether through complete or partial immunity), they also reduce the force of infection, lowering the risk of illness even among those with no immunity. ... So there will be a time after the pandemic when life returns to normal. We will get there even if we fail to develop a vaccine, discover new drugs or eliminate the virus through dramatic public health action, though any of these are welcome because they would hasten the end of the crisis. But a long and painful process may be in store first. The first pandemic wave might infect more than half the world’s population. ... This first wave alone will not get us to the point where covid-19 becomes a disease of children. An infection rate of 50 percent would leave half of adults at risk in the next wave. But a reduction in susceptible individuals would weaken subsequent waves. ... Eventually, we will reach a point where covid-19 deaths in the elderly are virtually unheard of — but this could take a decade or more. Development of a vaccine would vastly accelerate this process. ... Even without a vaccine, improved treatment and new drugs could substantially reduce deaths. There are countless efforts underway to develop vaccines and treatments, but these take time; pharmaceutical solutions may not be available fast enough to blunt the first wave of the pandemic. ... [T]hough it may be years in the future ... this once-dreadful disease will morph into a mild annoyance in the years to come." https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/coronavirus-pandemic-immunity-vaccine/2020/03/12/bbf10996-6485-11ea-acca-80c22bbee96f_story.html Sharing water is an increasingly contentious issue, even in water-rich Florida. This article profiles the battle between recreational users of Florida's natural springs -- including mermaids :-) -- private interests, including Nestle's spring-water bottling operation, and agriculture. "For Florida, decades of huge population growth and increased agricultural irrigation have reduced the levels of the Floridan Aquifer, an underground system of water-filled rocks that stretches 100,000 square miles and includes parts of southern Georgia and Alabama. The aquifer provides fresh water to millions of people in fast-growing cities like Jacksonville and Orlando. In northern Florida, it supplies the springs, which feed nearby rivers, like the Santa Fe River, that are popular ecotourism spots and help drive local economies. “It’s like a big Slurpee cup with about a million straws,” said Robert Knight, an environmental scientist who runs the nonprofit Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute. Dr. Knight estimates that as the demands on the aquifer have increased, average flows into the various springs have declined by more than a third. Some springs have dried up. Some coastal areas are seeing water that was once drinkable become contaminated with saltwater from the sea.

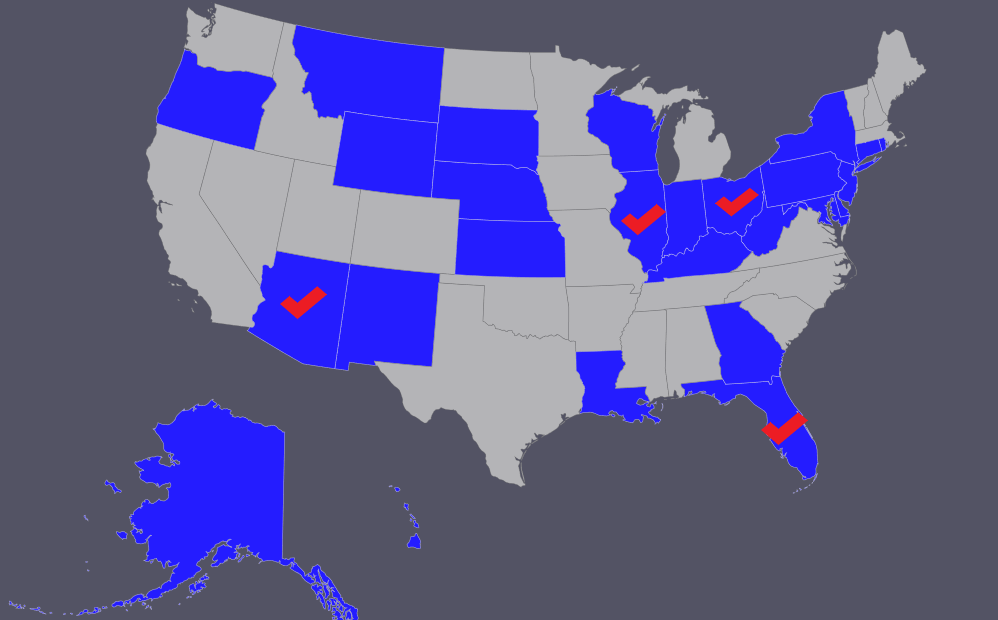

"In High Springs, the battle over water has sharply divided the small, rural community. On one side are environmentalists, who rail against the notion of a corporation using Florida’s natural resources for its own profit while adding to the problem of single-use plastic bottles. They are joined by local business owners who provide lodging, food and equipment rentals — canoes, inflatable tubes and diving gear — to the tourists who come from around the world each year to enjoy the natural springs. They are facing off against the Wray family, which has owned the popular recreational spot for generations. The Wrays argue that even the increased amount of water that will be pumped [1.15 million gallons per day] represents less than three-quarters of one percent of the water flowing into the nearby river from the springs on their property. Some family members say the real problem is overpumping by large agricultural operations. The family is joined by Nestlé, which says it is providing an essential and healthy beverage for consumers and creating well-paying jobs." www.nytimes.com/2020/03/08/business/nestle-florida-water.html "Social distancing" and voting do not go particularly well together. This map shows (in blue) the states that have not yet held their 2020 primary elections. The states with a red check mark are scheduled to do so tomorrow (March 17).

Moral intuition is a powerful, and highly variable, thing. We often decide right or wrong first and look for reasons to justify our position afterwards. A recent psychology experiment, though, suggests that at least some of our "moral intuition" is based on feeling physically queasy.

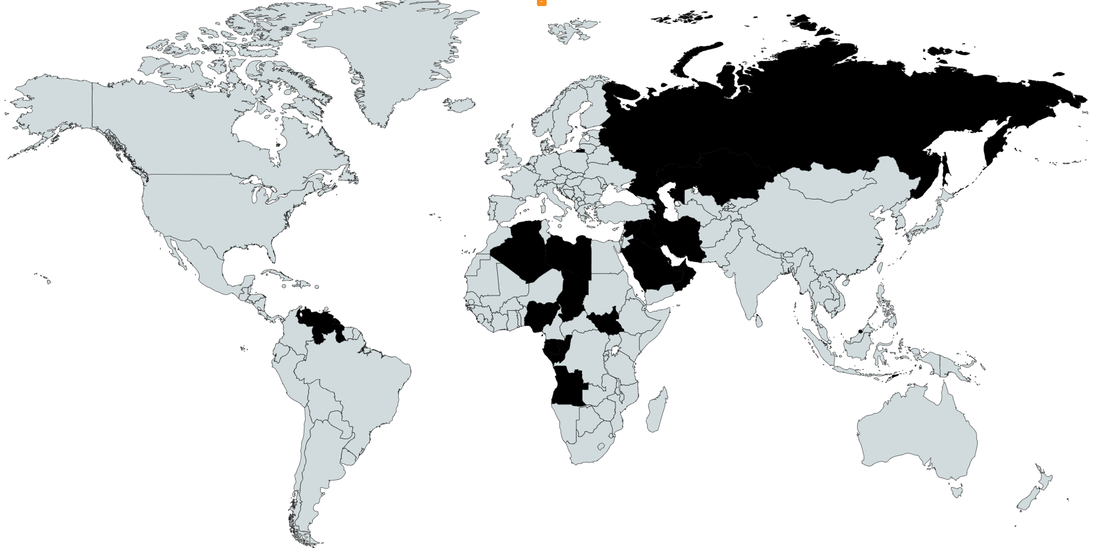

"There are, after all, practices that many of us deem morally wrong and disgusting, including sex with a close relative, but also touching a dead body, or eating a recently deceased pet. And the more disgusting we find these behaviours, the more wrong they seem.... This association begs the question: might our moral judgments come from the sickened way that morally improper behaviours make us feel? ... Until recently, no research study had been able to figure out if the disgust felt upon encountering a morally troubling situation is what makes us decide that the situation is wrong. In fact, no study had even determined whether that feeling is real – whether, when we say we are disgusted by some morally reprehensible event, we mean it literally: we feel nauseous. This gap in scientific knowledge led my former graduate student Conor Steckler to come up with a brilliant idea. As those prone to motion sickness might know, ginger root can reduce nausea. Steckler suggested we feed people ginger pills, then ask them to weigh in on morally questionable scenarios – behaviours such as peeing in a public pool, or buying a sex doll that looks like one’s receptionist. If people’s moral beliefs are wrapped up in their bodily sensations, then giving them a pill that reduces some of those sensations might reduce how wrong those behaviours seem. ... "Those who ingested ginger decided that some of those violations, such as someone peeing in your swimming pool, were not so wrong after all. Blocking their nausea changed our participants’ moral beliefs. Importantly, these effects didn’t emerge for all the moral dilemmas we presented. Prior to conducting the research, we had categorised hypothetical moral situations as either highly severe or only moderately problematic, based on research assistants’ judgments of wrongness. Having sex with a sibling and eating one’s dead dog were considered highly severe, but touching the eyeball of a corpse, eating faeces that had been fully sanitised, and buying an inflatable sex doll that looks like one’s receptionist were seen as more moderate. In our studies, ginger had no effect on participants’ responses to highly severe infractions. ... In contrast, for the more ambiguous infractions – such as buying that sex doll or eating (totally clean!) faeces – people’s moral judgments were partly shaped by their disgust feelings. In such cases, where disgust is elicited but wrongness is uncertain, people seem to lean on their gut emotions to make moral judgments. If those feelings are inhibited, so that people can think about the possibility of eating clean faeces without wanting to throw up, the objectionable behaviours become less morally problematic. We also found that ginger had no effect on people’s beliefs about other kinds of moral violations: those that involve harm to others, such as drinking and driving, or those that involve fairness, such as failing to tip a server. The violations that were affected by ginger, in contrast, centred on maintaining the purity of one’s own body. ... "[O]ur research shows that moral beliefs based on sanctity concerns represent a different category of morality than those based on harm and fairness. We were able to shift people’s sanctity beliefs simply by giving them ginger. A moral view that changes on the basis of how nauseous we feel is probably not one that we want to put a lot of stake in. Instead, many of us would prefer to hew to a set of moral standards that come from a coherent, rationally derived philosophy about enhancing justice and mitigating harms. ... Before deciding that something is wrong, we might ask ourselves, is it just that I’m disgusted by it? Or, when encountering what appears to be a moral dilemma, we could play it safe and reach for a ginger ale." aeon.co/ideas/find-something-morally-sickening-take-a-ginger-pill The collapse in global oil prices -- due in part to falling demand related to COVID-19 and due in part to a production battle between Russia and Saudi Arabia -- is a serious threat to the economies of the world's petrostates. A petrostate is generally defined as a country that derives a significant percentage of its GDP or national income from petroleum and related hydrocarbons. The world's major petrostates are shown on this map.

Stuck in the house? Explore.org is the world's largest wildlife cam network. Watch who comes and goes at a South African watering hole, bald eagles on their nests, the residents of a kelp forest, gorillas in the DRC, Florida manatees, and more. explore.org/livecams/

My "Your Future World" class was studying Indonesia this week. These maps track 70 years of deforestation on the island of Borneo, most of which is controlled by Indonesia (with smaller portions in the north controlled by Malaysia and the Sultanate of Brunei). i.redd.it/821p91ku0wf41.jpg

As the U.S. works to extricate itself from Afghanistan, "The ignominious end to the war in Vietnam haunts this discussion. Many Americans retain indelible images of North Vietnam’s devastating final offensive against the South, the complete collapse of the Saigon government and its army, and the desperate, belated efforts of Americans and South Vietnamese to escape the onslaught. For a nation accustomed to victory in war, such memories are searing. Would a withdrawal from Afghanistan look like Vietnam and have similar consequences for Afghans—and Americans?" This article from Foreign Affairs discusses ways in which Afghanistan is similar to and quite different from Vietnam as well as lessons learned from the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam that should be kept in mind as the U.S. negotiates withdrawal from Afghanistan. www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2019-04-15/lessons-vietnam-leaving-afghanistan

U.S. farmers have always changed their crops to suit markets and climate. This article looks at the shifts currently underway. "Geography isn’t static. Rivers change course, mountains erode, and islands disappear under rising seas. The geography of farming and food changes, too. For example, 180 years ago my home county was the castor bean and castor oil capital of the U.S. Both titles, however, slipped into irrelevance as a new resource, crude oil, rose to dominate the lubricant business. Today, fewer and fewer Americans have ever heard of castor beans or castor oil. Those long-forgotten twins seem to have a modern equivalent. Total U.S. wheat acres peaked at 88 million in 1981. Last year, the most recently completed reporting year, total U.S. wheat acres were about half of that, or 45.6 million acres. ... It’s no surprise that the two biggest benefactors of wheat’s decline are America’s two biggest crops, corn and soybeans. ... There are two critical (among other) reasons for the big switch: Government ethanol blending mandates have fueled corn’s rise and fast-growing soy exports, especially to China, have pushed soybean acres higher. Both forces, however, are losing steam. Increased use of electric cars and, soon, trucks, already has flat-lined the once-voracious U.S. gasoline — and, in turn, ethanol — appetite and continued global competition in the soy trade is pinching U.S. soybean margins toward break-even."

www.telegraphherald.com/news/agriculture/article_a0e4379b-2c3b-590c-8ae1-416b03271c22.html This map highlights the economic output of the U.S. Just 35 counties (of which 7 are in California) accounted for 1/3 of total U.S. economic output in 2018. howmuch.net/articles/americas-economic-output-2018

"Live bits of brain look like any other piece of meat — pinkish, solid chunks of neural tissue. But unlike other kinds of tissue or organs donated for research, they hold the memories, thoughts and feelings of a person. ... That uniqueness raises a whole new set of ethical quandaries when it comes to experimenting with living brain tissue.... These precious samples, normally discarded as medical waste, are donated by patients undergoing brain surgery and raced to the lab while the nerve cells are still viable.

"Other experiments rely on systems that are less sophisticated than a human brain, such as brain tissue from other animals and organoids. ...[W]ith major advances, these systems might one day be capable of much more advanced behavior, which might ultimately lead to awareness, a conundrum that raises ethical issues." As a result, neuroscientists are now working closely with neuroethicists to design and monitor experiments involving brain tissue. www.sciencenews.org/article/living-brain-tissue-experiments-ethics-neuroscience Tomorrow is the beginning of daylight savings time in those parts of the United States that adopt daylight savings time. Another time oddity is the International Date Line, the imaginary line that roughly corresponds to a longitude of 180°. The west side of the line is a day ahead of the east side of the line. Although the line jogs around certain political entities, it still creates for some curious situations, especially as far as islands are concerned. In the South Pacific, clocks in Tonga and American Samoa, for example, will show precisely the same time, but Tonga is a day ahead of American Samoa because, even though they share a time zone, Tonga is on the west side of the International Date Line. In the North Pacific, Big Diomede and Little Diomede are two islands that sit 2.5 miles apart in the Bering Strait but are separated by the International Date Line (and geopolitics). Big Diomede, part of Russia, is a day ahead of Little Diomede, which is part of Alaska, leading to their respective nicknames Tomorrow Island and Yesterday Island. static01.nyt.com/images/2012/07/31/opinion/31borderlines/31borderlines-blog427.jpg

|

Blog sharing news about geography, philosophy, world affairs, and outside-the-box learning

Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed