|

Most of the concern about "big tech" seems to focus on economic power and privacy. This article written by two Oxford University scholars working at the nexus of philosophy and international affairs raises a different question: what should be be doing to prevent the technological development that might lead to our destruction?

"One way of looking at human creativity is as a process of pulling balls out of a giant urn. The balls represent ideas, discoveries and inventions. Over the course of history, we have extracted many balls. Most have been beneficial to humanity. The rest have been various shades of grey: a mix of good and bad, whose net effect is difficult to estimate. What we haven’t pulled out yet is a black ball: a technology that invariably destroys the civilisation that invents it. That’s not because we’ve been particularly careful or wise when it comes to innovation. We’ve just been lucky. But what if there’s a black ball somewhere in the urn? If scientific and technological research continues, we’ll eventually pull it out, and we won’t be able to put it back in. We can invent but we can’t un-invent. Our strategy seems to be to hope that there is no black ball. ... "But one way to think about the possible effects of a black ball is to consider what would happen if nuclear reactions were easier. In 1933, the physicist Leo Szilard got the idea of a nuclear chain reaction. Later investigations showed that making an atomic weapon would require several kilos of plutonium or highly enriched uranium, both of which are very difficult and expensive to produce. However, imagine a counterfactual history in which Szilard realised that a nuclear bomb could be made in some easy way – over the kitchen sink, say, using a piece of glass, a metal object and a battery. ... [P]erhaps the US government would move to eliminate all glass, metal and sources of electrical current outside of a few highly guarded military depots? Such extreme measures would meet with stiff opposition. However, after mushroom clouds had risen over a few cities, public opinion would shift. Glass, batteries and magnets could be seized, and their production banned; yet pieces would remain scattered across the landscape, and eventually they would find their way into the hands of nihilists, extortionists or people who just want ‘to see what would happen’ if they set off a nuclear device. In the end, many places would be destroyed or abandoned. Possession of the proscribed materials would have to be harshly punished. Communities would be subject to strict surveillance: informant networks, security raids, indefinite detentions. We would be left to try to somehow reconstitute civilisation without electricity and other essentials that are deemed too risky. That’s the optimistic scenario. In a more pessimistic scenario, law and order would break down entirely, and societies would split into factions waging nuclear wars. ... In short: we’re lucky that making nuclear weapons turned out to be hard. We pulled out a grey ball that time. Yet with each act of invention, humanity reaches anew into the urn. "Suppose that the urn of creativity contains at least one black ball. We call this ‘the vulnerable world hypothesis’. The intuitive idea is that there’s some level of technology at which civilisation almost certainly gets destroyed, unless quite extraordinary and historically unprecedented degrees of preventive policing and/or global governance are implemented. Our primary purpose isn’t to argue that the hypothesis is true – we regard that as an open question, though it would seem unreasonable, given the available evidence, to be confident that it’s false. Instead, the point is that the hypothesis is useful in helping us to bring to the surface important considerations about humanity’s macrostrategic situation. ... It would be bad news if the vulnerable world hypothesis were correct. In principle, however, there are several responses that could save civilisation from a technological black ball. One would be to stop pulling balls from the urn altogether, ceasing all technological development. That’s hardly realistic though; and, even if it could be done, it would be extremely costly, to the point of constituting a catastrophe in its own right. ... That leaves two options for making the world safe against the possibility that the urn contains a black ball: extremely reliable policing that could prevent any individual or small group from carrying out highly dangerous illegal actions; and two, strong global governance that could solve the most serious collective action problems, and ensure robust cooperation between states. – even when they have strong incentives to defect from agreements, or refuse to sign on in the first place. The governance gaps addressed by these measures are the two Achilles’ heels of the contemporary world order. So long as they remain unprotected, civilisation remains vulnerable to a technological black ball. Unless and until such a discovery emerges from the urn, however, it’s easy to overlook how exposed we are." aeon.co/essays/none-of-our-technologies-has-managed-to-destroy-humanity-yet

0 Comments

The Gulf Stream, which carries 30x more water than all the world's rivers combined, has played a pivotal role in shaping climate, biogeography, and human civilization in Europe, North America, Africa, South America, and even Asia. Now, a growing body of scientific research is finding this critical conveyor belt of thermal energy is slowing and weakening. This article from The New York Times walks readers through the science and its implications. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/03/02/climate/atlantic-ocean-climate-change.html

In the U.S., lack of access to running water has tended to be associated with rural areas. But, as this geo-graphic based on a report prepared by the National Academy of Sciences shows, water insecurity in the U.S. is primarily an urban problem, with 73% of households that lack hot and cold running water located in cities, the majority of these being renters and people of color. cdn.statcdn.com/Infographic/images/normal/23731.jpeg

Looking for a way to introduce philosophy to elementary school children? Undercover Robot: My First Year as a Human might be just the thing: smile.amazon.com/Undercover-Robot-First-Year-Human/dp/1406388661/

The maps accompanying this article from The Wall Street Journal show the impact of the pandemic on air travel by comparing domestic and international air traffic in the U.S. and around the world on Feb. 26, 2021 with that of Feb. 28, 2020. www.wsj.com/articles/the-places-you-cant-fly-to-anymore-11616248802

For just $3 you can order a ~2'x3' color map showing all of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites (with a key identifying each site on the reverse). Or you can download one for free. Some of my geography students may recognize the Fujian tulou featured at the top of the map :-). whc.unesco.org/en/wallmap/

Although the kidnapping of schoolchildren by Boko Haram makes the news in the U.S., kidnapping schoolchildren has become regrettably common across Nigeria, including in regions far from where Boko Haram operates the northeast, as this map, from The Wall Street Journal, makes clear. "Since December, heavily armed criminal gangs have abducted and ransomed more than 800 schoolchildren, rocking Nigeria.... Hundreds of school campuses have been closed across four states for fear of more attacks, leaving close to 15 million Nigerian children out of school—more than any other country in the world. ... Nigeria’s wave of violent crime is widening an arc of instability that has spread into three of its neighboring countries: Niger, Cameroon and Chad." www.wsj.com/articles/kidnapping-schoolchildren-in-nigeria-becomes-big-business-11616511947

In January, the U.S. banned cotton from China's Xinjiang province -- which constitutes one-fifth of the world's cotton supply -- citing forced labor and other abuses of the region's Uighur population. This article looks at the impact of this decision on the global textile industry and its supply chains, including emerging technologies to verify the sourcing of a given shipment of cotton. www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-cotton-sanctions-xinjiang-uighurs/2021/02/21/a8a4b128-70ee-11eb-93be-c10813e358a2_story.html

The massive Hindu festival of Kumbh Mela is held on a 12-year cycle and attracts tens of millions of pilgrims, making Kumbh Mela the world's largest peaceful gathering. This year, Indian authorities will be struggling to balance a new surge of COVID infections with an estimated 150 million people expected to travel to and from Haridwar, in northern India, for the Kumbh Mela festivities that began earlier this month will continue into late April. (Biggest crowds are expected on April 12, April 14, April 21, and April 27.) www.financialexpress.com/lifestyle/travel-tourism/kumbh-mela-coronavirus-hardiwar-kumbha-meal-covid-updates-uttarkhand-tirath-singh-rawat-kumbh-shahi-snan-dates/2217214/

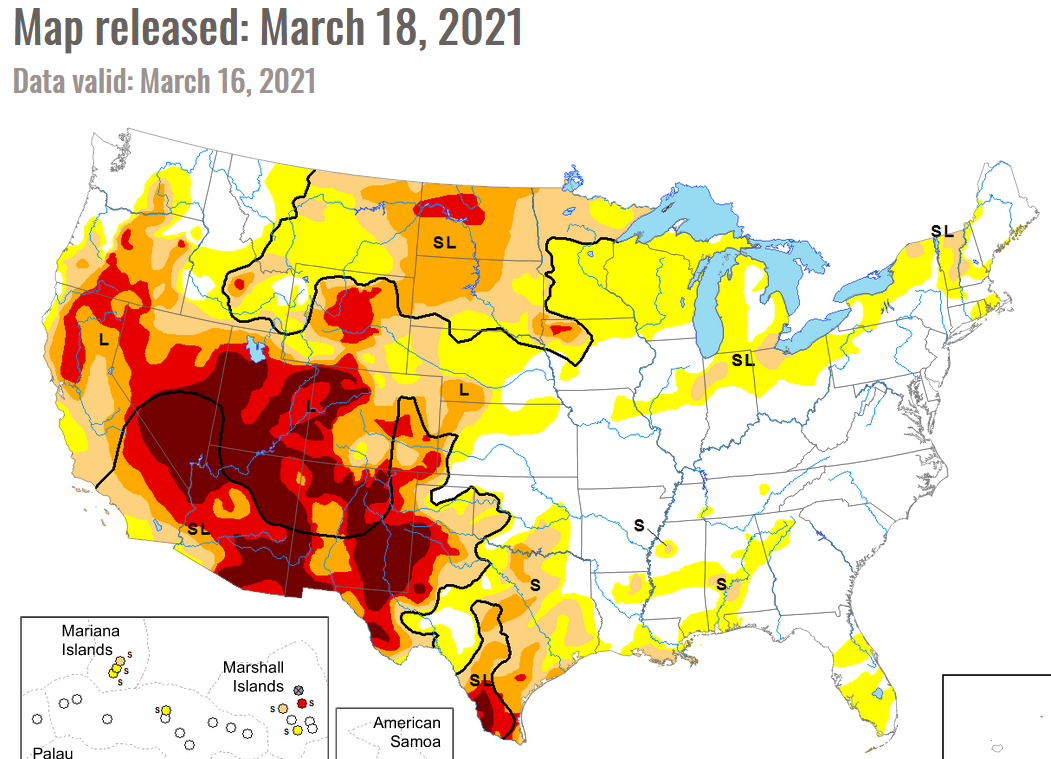

Wet winter or dry winter? According to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln's weekly drought monitor, in most of the western U.S., it was a very dry winter, with short-term droughts exacerbating long-term trends and dry conditions extending across the upper Great Lakes region. droughtmonitor.unl.edu/

Does moral culpability for harm require intent to harm? This piece from Yale psychologist Paul Bloom explores our different moral instincts when it comes to intent and outcome.

"There are two main considerations that we take into account when something has done wrong—the intent of the actor and the outcome of the action. To take the sort of example used in psychological research, Mrs. Smith thinks your child is allergic to peanuts, makes him a peanut butter and jelly sandwich with homicidal intent, and gleefully watches him die. This is murder. But what if she’s mistaken and your child has no such allergy? She watches with surprise as he says thank you and runs off to play. This is bad intent without a bad outcome. It’s awful but not as awful as murder. Now imagine a third scenario in which Mrs. Smith is unaware of the allergy and kills your child by mistake. Here we have a bad outcome without bad intent. But she would presumably be racked with guilt—and should be—and might still be charged with a criminal offense. To take a milder case, if you spill your coffee on my laptop, it matters a lot to me whether you did it on purpose. But even if it was a totally unavoidable accident, you should apologize and perhaps offer to help pay for the repair. Outcomes matter even in the absence of intentions. ... "There is a logic to this: Intentions are hard to infer and easy to lie about. Outcomes are observable by third parties and can form the basis of impartial judgment. And outcomes—the death of a child, a ruined laptop—are what matter. Indeed, it’s likely that we worry so much about intentions only because they are clues to future outcomes. If you intended to knock over my coffee, it raises the chances that you might do it again—or worse—in the future. ... "We [do] take intention into account, after all, for people we care about. For them, we are sensitive to nuance and purpose and inclined to give second chances. Zero-tolerance is something we reserve for strangers and enemies, either personal or political. Part of this might just be a desire to harm them, a delight in seeing them fired and humiliated. But deeper considerations are also at work. We don’t trust those we don’t like, and so we dismiss their stated intentions; we are more comfortable thinking of their suffering as instrumental, helping us to satisfy broader goals of deterrence.... And so, in the end, the argument for caring about intention is an argument for charity—for treating a stranger or even an enemy like someone we care about." www.wsj.com/articles/when-intentions-dont-matter-11615571956 Today is the vernal (or spring) equinox. The vernal equinox and the autumnal (or fall) equinox are the same in that both have equal amounts of day and night, but equal sunlight does not translate into equal temperatures, as this map of much of North America shows: www.alaskapublic.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/03202018_Climate2.jpg.

If you are looking for a citizen science project, SciStarter lists more than 1500 projects -- from mapathons to naturalist work to transcribing oral histories to psychology research and more -- all sortable by location, topic, and age range. I just sent a link for a citizen science project to my son in Missouri :-) scistarter.org/finder

Shutting off the internet has become an increasingly popular option for asserting governmental control. This geo-graphic looks at the countries in which people began searching for internet workarounds over the last year and indicates what was going on at the time: www.statista.com/chart/24122/vpn-search-during-internet-shutdowns

One of the enduring artifacts of the coronavirus pandemic is a decline in birth rates. In the U.S., for example, there were 300,000 "missing" births in 2020. In China, though, the pandemic hit when the country was already having limited success convincing couples, most of whom grew up as only children themselves, to have more than one child. China "faces a shrinking labor force, a skewed sex ratio and one of the world’s fastest-aging populations. Data released by the Ministry of Public Security in February showed a 15 percent drop in registered new births in 2020. ... Bleak demographic predictions have fanned fears that the country will grow old before it grows rich, as decades of restricting family size compound the effects of urbanization and growing wealth in curbing birthrates. China’s population could begin shrinking as early as 2027, according to an estimate from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and citizens over the age of 65 will account for 20 percent of the population by 2025. ... Urban couples especially, daunted by the cost and pressure of raising a child in China’s hypercompetitive cities, are increasingly forgoing parenthood. ... Others fear that officials will reorient the gigantic family-planning bureaucracy, which enforced restrictions through forced abortions, sterilizations and steep fines, toward pushing women to have children. Recent proposals to inspire more births range from lowering the minimum age for marriage to 18 (from 20 for women and 22 for men) to using education to encourage women between the ages of 21 and 29 to “give birth in a timely manner.”“I am pessimistic that lifting childbirth limits will put women’s status further behind. I feel like scenes from ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ could really happen. I just don’t know when,” [former journalist Chen Hongyu] said."

www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-child-policy-population-growth/2021/03/05/16dd613a-75b8-11eb-9489-8f7dacd51e75_story.html Greenland's snap elections scheduled for Apr. 6 are generating an unusual level of international interest, in no small part because of Greenland's emergence as a potentially significant source of rare-earth metals and the controversy surrounding the ownership, politics, and consequences of a huge new rare-earth/uranium mine being planned. foreignpolicy.com/2021/03/10/greenland-election-rare-earth-elements-china-us-europe

Spring is migration season in North America. Although some birds have already returned to their summer nesting grounds, most songbirds will not migrate until April or early May. This set of tools from Colorado State and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology provides bird migration maps and forecasts for the contiguous U.S.: birdcast.info/

In The Princess Bride, Vizzini asks, "Have you ever heard of Plato? Aristotle? Socrates?" and then dismisses them all as "Morons!" The line is funny, of course, because everyone has heard of Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates. But what about other philosophers of the ancient world? This article shares brief profiles of six women philosophers: theconversation.com/wise-women-6-ancient-female-philosophers-you-should-know-about-156033

This geo-graphic looks at extreme poverty around the world (measured as living on $1.90 per day or less). If one can believe the numbers, it is worth noting that China's extreme poverty rate is now the same as that of the U.S., Japan, Canada, and Norway, among others. The size of the circle in each band reflects the number of people in extreme poverty. howmuch.net/articles/extreme-poverty-around-world

Parents sometimes think that because their children have grown up with the internet, students can reliably find and distinguish credible online information. Having taught college-prep research and writing classes for years, I can confirm this is largely untrue. This video from Stanford University's library system aims to improve students' information literacy: www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZ122WakNDY [For more detail, this SUNY website walks students through a series of steps to help them determine if a given source is a credible source of information or not, with a short quiz at the end. subjectguides.esc.edu/researchskillstutorial/ch5]

What appears to be an accidental explosion at a military facility in Equatorial Guinea this week has claimed the lives of roughly 100 people and injured hundreds more. The explosion occurred in the mainland city of Bata, on the Atlantic coast. More than half of Equatorial Guinea's population lives in either Bata or the capital of Malabo, which, as this map shows, is not on the mainland (known as Rio Muni) but is instead on the nearby island of Bioko. Equatorial Guinea is actually not equatorial -- the Equator runs just south of the country -- but it is the only African country in which Spanish is the official language. www.worldatlas.com/r/w1200/upload/6e/ee/19/gq-01.jpg

The biggest, fastest asteroid likely to approach the earth this year is expected to sail by in 10 days. Asteroid F032 was spotted almost exactly 20 years ago and has been monitored ever since. Although it is moving at roughly 100 times the speed of sound and is rated as "potentially hazardous" by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, F032 is expected to remain at least 1 million miles from earth. However, recognizing the threat asteroid collisions have been to life on earth previously, NASA is studying means of deflecting asteroids that might one day be on a collision course with earth. www.livescience.com/potentially-hazardous-asteroid-whizzes-near-earth-2001-fo32.html

This article from The Wall Street Journal looks at how a year of remote work for 50% of the workforce has changed where we live:

"This rapid reordering accelerates a trend that has been under way for years. And it doesn’t just change the dynamic between workers and companies. It is affecting the economic fates of cities and communities large and small, but especially smaller ones: They can now develop and build their economies based on remote workers and compete with the big-city business centers and West Coast high-tech meccas that have long dominated the employment landscape. Smaller metro areas such as Miami, Austin, Charlotte, Nashville and Denver enjoy a price advantage over more expensive cities like New York and San Francisco, and they are using it to attract newly mobile professionals. Smaller cities like Gilbert, Ariz., Boulder, Colo., Bentonville, Ark., and Tulsa, Okla., have joined the competition as well, some of them launching initiatives specifically designed to appeal to remote workers. And more rural communities including Bozeman, Mont., Jackson Hole, Wyo., Truckee, Calif., and New York’s Hudson Valley are becoming the nation’s new 'Zoom towns,' seeing their fortunes rise from the influx of new residents whose work relies on such digital tools. ... Such changes may begin to reverse the increasingly winner-take-all nature of America’s economic geography. In the decade and a half leading up to the Covid-19 pandemic, more than 90% of employment growth in America’s innovation economy was concentrated in just five coastal metro areas: San Francisco, San Jose, Seattle, San Diego and Boston, according to the Brookings Institution. ... For cities, remote work changes the focus from luring companies with special deals to luring talent with services and amenities. Communities can invest precious tax dollars more wisely and cost-effectively on things like better schools and public services, parks and green spaces, safer streets, bike lanes and walkable neighborhoods. ... "Over time, the competition for talent could shift to places that offer the best combination of quality of life, affordability and state-of-the-art ecosystems to support remote work. Before the pandemic, a number of communities developed strategic initiatives to attract newcomers—some aimed at high-tech workers but others open to anyone who commits to moving. Many include the lure of cash incentives, akin to the moving expenses paid by companies to new hires. The programs’ perks and requirements vary. 'Remote Tucson' offers $1,500 in cash and employment help for spouses; Hamilton, Ohio, covers up to $300 a month in student loans for nearly three years for recent graduates in science, math and tech fields; Savannah, Ga., reimburses $2,000 in moving expenses for new arrivals with three years’ experience in tech fields. 'Tulsa Remote,' established three years ago, pays remote workers who move from outside the city $10,000, plus access to affordable housing. (The costs are underwritten not by city hall but by a foundation.) ... To lure and support the growing ranks of remote workers, communities will need to build out more complete ecosystems for them to live, work and gather. First and foremost, that means ensuring adequate broadband connectivity. As the pandemic fades and people venture back outside, it will also mean ensuring the availability of abundant co-working spaces and “third spaces” such as cafes and restaurants, where remote workers can mingle and meet, and outdoor recreational spaces where they can go to recharge their mental batteries." www.wsj.com/articles/how-remote-work-is-reshaping-americas-urban-geography-11614960100 Last March saw a sharp rise in unemployment throughout much of the U.S. This map looks at the highest (in dark red) and lowest (in pink) unemployment rates across the 389 metropolitan areas of the U.S. as of December 2020. howmuch.net/articles/us-unemployment-rates-metropolitan-area

Epistemology, the branch of philosophy that considers how we "know" things, has traditionally emphasized individual knowledge. This important article by University of Connecticut philosophy professor Michael Patrick Lynch notes epistemology's growing interest in studying social knowledge and why this is crucial now.

"In the jargon of academia, the study of what we can know, and how we can know it, is called 'epistemology.' ... Interest in how knowledge is acquired and distributed in social groups has long been a substantive field of inquiry in the social sciences. But with notable exceptions—such as W. E. B. DuBois, John Dewey, Thomas Kuhn, and Michel Foucault—twentieth-century philosophers mostly focused on the individual: their central concern was how I know, not how we know. But that began to change near the end of the century, as feminist theorists such as Linda Alcoff and Black philosophers such as Charles Mills called attention to not only the social dimensions of knowledge but also its opposite, ignorance. In addition, and working largely independent of these traditions, analytic philosophers, led by Alvin Goldman, launched inquiries into questions of testimony (when should we trust what others tell us), group cognition, and disagreement between peers and experts. The overall result has been a shift in philosophical attention toward questions of how groups of people decide they know things. This attention, not surprisingly, is now increasingly focused on how the digital and the political intersect to alter how we produce and consume information. This interest is on display in Cailin O’Conner and James Weatherall’s recent book The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread (2019), as well as in C. Thi Nguyen’s work on the distinction between echo chambers (where members actively distrust “outside” sources) and epistemic bubbles (where members just lack relevant information). These examples highlight how philosophy can contribute to our most urgent cultural questions about how we come to believe what we think we know. ... "Democracies are especially vulnerable to such [epistemic] threats because in needing the deliberative participation of their citizens, they must place a special value on truth. By this I don’t mean (as some conservatives seem to think whenever progressives talk about truth) that democracies should try to get everyone to believe the same things. That’s not even possible, let alone democratic. Rather, democracies must place special value on those institutions and practices that help us to reliably pursue the truth—to acquire knowledge as opposed to lies, fact rather than propaganda. The epistemic threats to democracy are threats to that value and those institutions. ... "Research on 'epistemic spillovers' indicates how deeply politicized knowledge polarization really is. An epistemic spillover occurs when political convictions influence how much we are willing to trust someone’s expertise at a task unrelated to politics. In one study that explored how this works in everyday life, participants were able to learn both about the political orientation of other participants, and their competency at an unrelated, non-political task (often extremely basic, such as categorizing shapes). Then participants were asked who they would consult to aid them in doing the task themselves. The result: people were more likely to trust those of the same political tribe even for something as banal as identifying shapes. And they continued to do so even when they were presented with evidence that their political cohorts were worse at the task and even when there were financial incentives to follow that evidence. ... "[P]erhaps no attitude is more toxic than intellectual arrogance, the psychosocial attitude that you have nothing to learn from anyone else because you already know it all. ... But the real political problem is not arrogant individuals per se, but arrogant ideologies. These are ideologies built around a central conviction that 'we' know (the secret truths, the real nature of reality) and 'they' don’t. To those in the grip of such an ideology, countervailing evidence is perceived as an existential threat ... it encourages in its adherents what José Medina has called 'active ignorance.' Arrogance engenders entitlement, and entitlement in turn breeds resentment—forming the poisonous psychological soil for extremism. ... "Put slightly differently, what we really need to understand is how big political lies turn into convictions. A conviction is not just something one 'deeply believes' (I believe that two and two make four but that isn’t a conviction). A conviction is an identity-reflecting commitment. It embodies the kind of person you aspire to be, the kind of group you aspire to be a part of. Convictions inspire and they inflame. ... But Big Lies also do something else: they defray the value of truth and the democratic value of its pursuit. To understand how this works, imagine that during a football game, a player runs into the stands but declares, in the face of reality and instant replay, that he nonetheless scored a touchdown. If he persists, he’d normally be ignored, or even penalized. But if he—or his team—hold some power (perhaps he owns the field), then he may be able to compel the game to continue as if his lie were true. And if the game continues, then his lie will have succeeded—even if most people (even his own fans) don’t 'really' believe he was in bounds. That’s because the lie functions not just to deceive, but to show that power matters more than truth. It is a lesson that won’t be lost on anyone should the game go on. He has shown, to both teams, that the rules no longer really matter, because the liar has made people treat the lie as true. That’s the epistemic threat to democracy from Big Lies and conspiracies. They actively undermine people’s willingness to adhere to a common set of 'epistemic rules'—about what counts as evidence and what doesn’t. And that’s why responding to them matters: the more folks get away with them, the more gas is poured on the fires of knowledge polarization and toxic arrogance." bostonreview.net/philosophy-religion/michael-patrick-lynch-value-truth |

Blog sharing news about geography, philosophy, world affairs, and outside-the-box learning

Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed